Good in Theory: A Political Philosophy Podcast

Good in Theory: A Political Philosophy Podcast

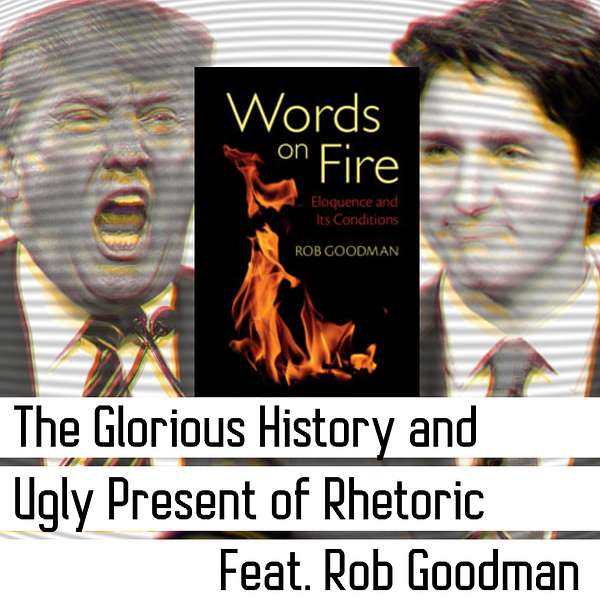

39 - The Glorious History and Ugly Present of Rhetoric feat. Rob Goodman

Rhetoric is supposed to inspire. Imagine Cicero exhorting the Roman people, Churchill vowing to “fight on the beaches.” Yet, when politicians speak today, it’s almost always boring or obnoxious. Why?

Prof. Rob Goodman, author of Words on Fire: Eloquence and its Conditions comes by today to talk about the history of rhetoric, what Cicero knew that we don’t, and the political speech styles of Trudeau (boring), Trump (obnoxious), and X González (pretty great, actually).

Today, why political rhetoric should be a resource for a galitary in politics, but instead is usually boring or obnoxious unplug mark. And this is good in theory, Rob Goodman. Welcome to good. In theory, you are a professor at Ryerson university, author of a book called words on fire eloquence in its conditions. And prior to that, a political speech writer. Uh, am I right? Yes. That's that's correct. And thanks for having me on by the way. Oh, you're very, very welcome. We're glad, we're glad to have you so. Tell me a little bit about, your practical background about, the speech writing part of it. Yeah. Well, I was a speech writer on Capitol hill, uh, for about five years. I worked on the house side and the Senate side, uh, worked for Krista and the Senate and Steny Hoyer. Who's a Nancy Pelosi's number two. And back then, I guess still is, uh, in the house. Um, and, uh, You know, a pretty steady basis, you'd write one speech or a statement or press statement or flora statement or speech for an outside broker, just maybe a couple of times per day. So you're turning out a really large quantity of words, uh, you know, kind of select number of themes because each have those sort of ed issues every day. Um, and, um, I was there in the late Bush years and the early Obama years. Um, I think probably the highlight of being there in that period, uh, was being there during the, uh, debate over the affordable care act. Um, and, uh, getting actually to be on the house floor when the affordable care act passed. That that was, that, that was a neat thing. Um, I, I'm glad that, uh, I'm glad to have, you know, in a teeny tiny way to have been part of that. Um, so after about five years of that, I, I realized I was going to a grad school part-time I was taking a part-time master's course in philosophy and fellow policy at the GW university in DC. Um, which sort of made me realize how, what I had really wanted to do was be an academic, uh, and that I really missed that world and kind of. I remembered a lot of that. Um, taking some part time courses and I decided to make a change, um, and, uh, uh, get back into academia. Um, so I went for my PhD, uh, at Columbia and I studied political science and political theory. Um, and as I was trying to figure out what I wanted to make the focus of that research, uh, and what did I wanted to work on? Um, I realized that there was a real opportunity here to connect what I had done in my past professional life, uh, to what I wanted to do as an academic, trying to figure out what was my thing was going to be. Um, you know, partly because I, I didn't want the time. Doing rhetoric from the practical side to go to waste. I thought I could inform what I had to say about rhetoric and political theory and in some unique ways that not a lot of people working in that area, uh, might've had the opportunity to do, um, th there aren't a lot of opportunities to write. Um, in theory about something you, you, you've seen a little bit more up close in practice. So I like to think that what I'm doing, um, when I think about rhetoric and political theory is at least a little bit informed by the time I spent in us politics. And that I can write, um, about rhetoric and political theory with a little bit of the authority that comes from having done it, which I think mainly just means in practice that I try to be my own BS test. I try to think if, uh, what I'm talking about, about the theory of rhetoric, uh, and about, uh, the development of rhetoric, um, over the long course of Western political thought. Um, if it really makes sense, uh, to something. Who's engaged in day-to-day practices of political persuasion, whether it's a social media or speech writing or speech making or community organizing or whatever it is. I try to apply that test to the extent that I can, which I hope makes what I have to write, um, more relevant to people in that world, or I guess that remains to be seen. But at least that, that was what I was thinking when I tried to make that connection between what I had done as a professional at what I'm now trying to do is academic. Well, I think that's, I mean, that's, that's great because. Not that many theorists have practical experience of, uh, of any kind much less. The other thing that theorizing, right? I mean, I did, my dissertation was about honor and dueling and, uh, well, I, I do not think that I lacked dignity more than a regular human being. I haven't funny duels, but there's, there's still chance. I, you still seem like a young guy, you never know. Right. Well, you know, you can issue the challenges, but, uh, yeah, I think I, I'm not an expert on this, but I think you need a glove. I wish I had a glove around here, but, uh, yeah. Yeah. They're, they're great for throwing on the ground. Your book words on fire eloquence in its conditions is about rhetoric. And I just want to start by specifying what you mean because the word rhetoric, uh, could be used in a lot of contexts. You're talking about political rhetoric and even political rhetoric. It could be in newspapers and op-eds in memes on social media. It can be almost anywhere, but. You're mainly concerned with the kind of paradigm type of political rhetoric. So you talk about Cicero a lot in the book, you can picture Cicero at the rostrum, addressing the Roman people, trying to rile them up to do something. Uh, and if they like what he's saying, they'll cheer him and, uh, claim him. And if they don't, maybe they'll heckle him, throw cabbage, Migo, assault him after bad things could happen. Now, traditionally rhetoric of this kind, this kind of persuasive political speech has been really important in politics and an important part of the gentleman's at education, but in philosophy and in common thought rhetorics being suspicious, right? Because if these speakers they're stirring up everyone's emotions, they're trying to get them to do something. Why isn't it just manipulating. Shouldn't they be addressing the people's reason. So you don't think that rhetoric is bad this way. So tell me, um, why isn't rhetoric just manipulation. Why do you think it can play a positive role? Yeah, so I, I think first of all, you're absolutely right that the kind of manipulative, or, you know, emotionally manipulative speech you're talking about definitely exists. You know, it absolutely is a thing out there in the world. Um, and one of the things I'm concerned with in the book is trying to figure out how, why it happens, what we can do about it. Um, but I will say that I tend to think of, of rhetoric, um, on the whole. As a good thing. And I guess the reason I do is because there, there isn't really any other means of making large scale collective decisions. You know, I think about rhetoric as a way of, of collective decision making is a way of trying to figure out what we in a given group are going to do it. It has to do it with judgment. It has to do with thinking together in public. Um, and of course there are bad ways of doing it. And of course there are bad ways of thinking together in public justice. There are kind of, um, Dom or fallacious ways of thinking as an individual. Um, so I don't think that the existence of those means of the whole thing is kind of a duped enterprise, but I do think that there are resources in the history of thinking about rhetoric that help us to, um, uh, help us to try to have more of the good and less of the bad. You know, one thing that I really take from, uh, from Brian Garston who wrote a really influential book on rhetoric that I draw from that really influenced me called saving persuasion. Um, When we're using rhetoric, what we're trying to persuade people by starting with what they think and what they believe and trying to get them where we want them to go. Um, trying to connect the belief that we're trying to inculcate, uh, with where they already are, but it, but if you're taking that step, you're already showing a lot of regard for them as your fellow citizens, um, as potentially political equals as, as people that you take seriously, because you have to take people's starting points and their beliefs and their values and their emotions. Seriously. If you really want to have a hope of persuading them. So even though that there are plenty of forms of manipulative and anti-democratic rhetoric, I think the whole premise that you can use. Words, uh, to move people, um, starts from a basic regard for, um, for the people you're dealing with. You, you can't even hope to succeed a rhetoric unless you have some kind of basic concern and care for, you know, the people in front of you. Of course, that could be distorted manipulate in all sorts of ways. But, but that's, I start from that basic concern care. Great. I want to follow that up a little bit because I get the argument that in order to persuade people, you have to have some concern for what they care about and what will move them. And that's fine. And so even in order to make an appealing speech and a persuasive speech, you have to appeal to these things that they already care about. But my question is, if you care so much about the audience, then why don't you just tell them the facts and let them decide because the practice of rhetoric, isn't just that, right. Uh, you talk about. Stylistic abundance. And I would say that if you give Cicero as an example, his speech is really extra. He's always adding in flamboyant examples and fancy language. Uh, and it's not just that, but as you know, from Aristotle persuasive speech, isn't just about the argument. It's also about showing that you're a persuasive, trustworthy speaker. That's ethos. It's about the character of the speaker. And so in today's rhetoric, when people say, you know, as a person of color or, uh, as, uh, someone with working class roots, politicians are saying this all the time, they're establishing their character, that they're a trustworthy person, and that doesn't always have to do with the facts of the case. Um, and Aristotle is also saying that you have to appeal to the motions. His guide's rhetoric is, uh, in large part about how to appeal to people's emotions. So. The question is if you care about your audience and you want them to have good decisions, why are you using all these persuasive techniques that go beyond just giving them a straight up argument facts, reason that would allow them to make the best decision for them? Yeah. Well, I think part of the reason is the things that kind of fit go into that quality of, of extra, you know, like for instance, uh, emotions or, you know, or ethos, the character of the speaker, how you show who you are and the way that you talk. Um, I think Aristotle was right to say that these things aren't totally irrelevant, even if they're not part of, part of a, uh, an argument per se, because, uh, they, they tell us what we value about the world. They tell us, um, uh, they orient us to what's important. Um, they orient us to whether we can trust this person speaking in front of us and all these things are kind of beyond the level of BD logical argument, but they still affect how we happen to judge as individuals. So I think part of the answer is sort of a realist answer is just like, look, this is just how we judge we're emotional creatures. We have these emotions, we have these, um, is this wanting to evaluate people on the basis of their trustworthiness? You, you, you can, um, you essentially can't get around it cause that's how we, we are. But you know, even beyond that, I think that there are, um, uh, One that our emotions and our evaluations of character kind of show what we value and what's important to us. And I also think that this, you know, the stuff that goes in the category of stylistic abundance, the, the extra, the, the stuff in which order is actually kind of attempt to be eloquent, um, says a lot about how they're accommodating to that audience, because every audience they talk to is going to have a different idea of what sort of language is appropriate. Uh, what sorts of figures of speech move them and don't move them. Um, what counts is just the facts? I don't think there's this sort of like pre political pre rhetorical, just the facts that they're lying, or you can pick up. I think you have to figure out what counts is that in any kind of given encounter with an audience. So I think that the number one reason that I think this stuff has been valued in history of rhetoric and in why I continue to value it is because a lot of it has to do with, with this value of ACP. Uh, accommodating an audience, a speaker, uh, learning about the people in front of him or her, and demonstrating a regard for them in the process of trying to win them over. Um, and, and you know, that that's part of what makes rhetoric complicated. And that's part of what creates a sort of stylistic abundance. But I don't think it's just there for show or just there to make people sound pretty. I think it's there because it really comes out in the process of the speaker, learning about what moves the audience and trying to reach an audience, um, uh, on the level of, of, of emotion and style and language and character, which, which matter whether we want them to matter or not. So no matter what we're doing rhetoric, there is no, there is no, there is no outside of rhetoric. So we might as well do it. Well, I think that started to say, I think. Um, you know, like I said earlier, I think there are kinds of forms of communication that aren't rhetorical. Um, you know, I think a conversation isn't like rhetoric for some interesting reasons. I think, you know, geometry, um, uh, you know, logic, certain kinds of coming to arguments and, and, and, and demonstrating proofs aren't rhetoric, uh, in some interesting ways. But I think in general, when we're deliberating together about politics, we, we are doing rhetoric. And that means that our, our emotions, that, that tell us what we value, whether it's our, our, our family or our, uh, home or, or, um, higher ethical values. Right. Those are, those are in there. Um, of course there are manipulative ways to appeal to those, but they're also in a non-manipulative ways. And I think that just, um, given that those appeals are going to exist in rhetorical speech, that that's why it's kind of worth learning about how to do it well, and by, well, I mean, both kind of stylistically well and hopefully ethically well. Right, right. Well, I mean, I don't know. I sometimes get sick of hearing of hardworking Canadian families. We're all working, we're all working so hard. Right. Sure. Right, right. No, I bet. Yeah. I, I, I, I hear ya. That's another one. If you say I hear you, or I get it that that's a pile politics demonstrates their, their, um, uh, sympathy for the message I care. Right, exactly. Uh, so in the book you talk about times when rhetoric goes, well, it can. It can realize these kind of a Galatarian political goals, hopefully. So it's effective, it can be ethical. And you talk about this in term of, of, uh, an interesting concept that you have called a rhetorical bargain. So could you explain what the rhetorical bargain is and, uh, give us an example of rhetoric doing what post to do. Yeah, yeah. So, so the first, I think to explain this idea of a rhetorical bargain, I think it's basically the idea that as I described, especially coming out of the classical world rhetoric is this, this asymmetrical situation, um, the few speak, but many listen, um, and from any kind of perspective, interested in some kind of basic political equality, but that that's not ideal. That's not great. Um, you want to think of ways of potentially flattening that divide. You want it to think of ways of potentially bringing some equity to an inequitable situation. Um, and then the thing that I think emerges from people thinking about rhetoric. Uh, under conditions of inequality, um, people like Mrs. Rowe who are not a Democrats and not a galitary ones, but still have some reasons to want it. The situation to be a little flatter is this idea of rhetorical bargain, this idea of risk on both sides of the equation, uh, different kinds of risks that are appropriate to different places in the rhetorical situation. Um, so I think for the audience, listening to something that might change your mind, exposing yourself to the possibility, uh, that you've been. Um, and you're going to announce your past, are you using the basis stuff that you've heard that's risky and it's potentially dangerous, it can upset your notion of who you are and what you value. Um, for the speaker, I think there's a different kind of risk. It's this risk of, uh, being publicly rejected of being humiliated of losing face for someone like Cicero and that this might connect with a little bit about, um, what you've studied and thought about on the idea of honor for someone in a situ in a society that highly values, um, ideas of honor, or veer twos, which is connected to the ideal of Manliness, um, losing face publicly, uh, is a big, big deal. Um, and this is something an orator takes on and risks, or at least ought to risk. Um, every time he or she speaks up in public, um, that's I think how the bargain ought to work. So one of the examples I think about in the book, um, of this barking going well at us, of course, is sort of the. Classic speech that everyone looks to in the ancient world, to speech on the crown, um, in which he's, uh, justifying, uh, this policy, um, of resisting. Um, what he sees is the tyranny coming from Philippa, Mastodon and threatening submerge Athens for all these years, even though the policy has failed, he's still trying to defend it and sort of making this sort of heroic, uh, rhetorical last stand. Um, and there's this, uh, moment, um, uh, that's called the oath on the heroes of marathon that gets quoted and all these ancient rhetoric, uh, treatises in textbooks and in the dye and the treatise on the sublime, sort of the famous moment in this, um, in which he swears by all the dead Athenian heroes of the past, um, um, That you are the current people of Athens, uh, haven't done anything wrong and that you've done the right thing, even though your policy has failed, that you, you did what was right. Uh, despite your failure. Um, and so the reason this is interesting to me is one, uh, it's obviously a tremendously, uh, risky move for him, um, because he is invoking sort of the, the highest civic ideals, the sort of ultimate symbolism of the golden age of this democracy that is now passed and gone, uh, invoking it to defend his own failed policy. Uh, you know, there's a polyp possibility that this thing could have gone very badly, that he could have been booed off the stage, which, which oftentimes people are when they attempt something, um, that is trying to venture into this territory, to the sublime of the, kind of over the top and the excessive. Um, there's also though, I think it's a great example of the connection between rhetorical form and content. So this idea of the. The form that he's using, the figure speech that comes into play there as is the idea of an apostrophe, which, which in a rhetorical theory means you are swearing by or invoking someone that that's not present. It's it's often kind of considered in ancient times was considered sort of the, the at the high doses of blind, because you're calling on the gods are calling on that real look dead to witness what's going on. Um, so one, it's kind of a form that embodies this idea of sublimity, but two, um, it's, it's directly connected to the idea that he thinks that the, the past, um, Athenian heroes were worth swearing by, and this was an appropriate occasion to invoke them. So if you were to just say without, you know, as, um, the person who wrote the treatise on the sub-line imagine what if you would take that part out and what if you had just said kind of flatly. Not, I swear by them that you did the right thing, but, uh, they did the right thing. And so did you, if you send it and kind of more, just the facts way, um, cause interesting observation on this as well, we really wouldn't be just the facts anymore because the implication would be the, he really didn't mean it. If, if you said something that was that kind of, um, that risky and that dangerous and that kind of, um, striving for sublimity in matter of fact terms, it would kind of indicate that you didn't really believe what you were saying would indicate that, um, uh, your, your heart wasn't in it and it was sort of a kind of transparent ploy. So this sort of connection, I think, between, um, the necessary form of the necessary content, it's the kind of example of how, um, form isn't this sort of extraneous thing to kind of sits on top. The meaning of our words, it's a way of expressing what we mean and how we mean it. Um, and I think the reason this gets singled out by, by lots of ancient writers who think about eloquence is just sort of this, you know, paradigm example of how you use the form of your words, not just to elicit an emotional response and get goosebumps. Um, but how to convey a, you know, kind of set of complicated ideas that are almost can't be expressed straightforwardly because to express them straightforwardly would be to kind of miss out on the idea that you're trying to advance. Right. Okay, great. So they're important things that just matter of fact, plain language cannot express. I think that you, you have to use rhetorical forms in order to get it yeah. And get the job done. I think that's fair to say, because I think there's, you know, the, the meaning of things, isn't just kind of the straightforward, semantic, meaning, it's the kind of what it means for you and what it means for us in this situation. Uh, and that there are some things that, um, that you don't really mean, unless you say them with the form of the, kind of. Matches the content you, you could just think of, you know, you, you could, um, tell a loved one that you love them, but if you're not making eye contact and you're saying in a kind of, sort of flat monotone way, and you're, you're, you're looking away and you're actually mean it. Um, it's not just the semantic content of the words. It's, it's the way in which you express them. That is part of the message that gets sent. And of course, you know, I think rhetoric is all about finding much more complex ways than that, that, that foreign content back each other up. Okay. And so in that example, could you give us an explanation of that in terms of the rhetorical bargain that we were talking about that makes a rhetoric a resource for and politics? Yeah. So I think, you know, part of the reason I look to the Roman situation for the, the, um, rhetorical bargain is it, I think it speaks a lot more to us is that it's kind of an oligarchic Republic rather than a direct democracy, but, you know, in the Damascus situation, You're you're, you're theoretically in a direct democracy in which kind of any Athenian male can get up and speak in practice though. It's kind of a limited number of people who have the ability, the training, you know, the, the leisure, the, the recognition to get up and address the assembly. So despite the fact that you've got formula quality, you've still got some kind of informal inequalities who can speak. So, so the idea that is a trained, effective elite speaker from a wealthy family with, with rhetorical training means that he's kind of one of a few people, a relative few people who can regularly address the assembly. So that's part of the asymmetry is based into, it's not just the idea that he is speaking and, you know, maybe 10,000 or 5,000 or however many people are listening. Um, it's that, he's one of a smaller number of people who could potentially speak. So you've got the situation of asymmetry baked into it. So how do you, how do you bridge that a little bit? I think part of the way you bridge it is by saying. That I, the person who I'm claiming the privilege to speak to you, I'm going to put some skin in the game. I'm going to accept a comparatively higher risk. Um, so in his case, um, it's, it's the, the risk of any particular kind of rhetorical gesture. And, you know, like I said, you know, swearing on the dead heroes to kind of endorse your policy is, is such a risky move that if enough people didn't buy it and you know, of course these things can kind of, there can be tipping points if you know, 50% plus one don't buy it. Um, you, you could conceivably be laughed out, shut it down, heckled that this happens all the time. In, in the Athenian context, people are always, um, shouting down heckling speakers. Uh, you know, he's giving this speech, uh, in a trial. So if he loses, um, there are potentially legal consequences, you know, up to and including, I'm not sure what the stakes for him were in this particular case, but up to, and including, um, exile, uh, heavy fines, uh, worst. So in many ways you're kind of pleading for your life. So these heavy penalties applied to the elite that don't apply to the average Joe or Demetrius or whoever it is in the audience. Um, so what was the audience putting on this steak? I think they're putting at stake these smaller, but still important risk of, uh, of listening of re-evaluating, uh, what they had thought in terms of, um, uh, In terms of what they're hearing, you know, in this case, the Moston is kind of arguing from position a weakness because, uh, he had been associated with this, this exceptionally aggressive, um, interventionists, anti massive on policy, uh, that, that seems to be crumbling, uh, that it seems to lead to Athens losing its political independence, um, he's in trouble. Um, and if you're an average member of the assembly that believes this, and you are still opening yourself up to the possibility that maybe you got it wrong and it might be otherwise, you're willing to be persuaded. I think of that as a risk too, because it's, it's the kind of risk to your, uh, integrity as a, as a political person. It's a risk to your, um, uh, to the story you tell yourself about who you are and what you value in politics. It's not the kind of risk of getting exiled, but I think it's appropriate to put the big, a risk on the positions of bigger privilege, which is kind of what this rhetorical bargain does. You know, for me, an example, um, and I, I like the example you brought up about, you know, telling the different ways you can tell someone that you love. Uh, that might be mean different things, right. And this, that same example would illustrate here the vulnerability of the speaker, because if you tell someone you love them and they throw cabbage at you and heckle you out of the assembly, um, you know, right. It's it's, it's not going to go well, there is a vulnerability there, right? Can you give me an example of a modern, good rhetoric of eloquence? So people might talk about Martin Luther king or JFK, or even Obama, uh, give me an example in living memory of modern day eloquence. Yeah. Well, I, I was thinking about this, um, and actually, if you want to tell me about one of your speeches I think mine are pretty forgettable. Um, um, but I, you know, there is an example that I didn't find a way to work into the book, but it really kind of struck me as, as illustrating this kind of riskiness and how it plays out. Uh, what was the example of him a Gonzalez in the, uh, the March for our lives? When we, one of the, um, um, protests against gun violence that came out of the, the, uh, Parkland shooting in Florida. Um, and I thought about this quite a bit as a modern example, because I don't really look to, um, most mainstream politics as demonstrating eloquence in the way I think of it, you know, for some of the reasons I talk about in the book, I think there are a lot of reasons that, um, you, you don't see eloquence for the most part of the political mainstream, because there isn't much of an incentive or reason to pursue it. And there isn't much of a culture around it. Um, so there there's a lot of culture of risk avoidance or a culture of, of demagogic speech that has its own problems. So I, you know, I really think that for the most part, if you're going to look to speech in the tradition of eloquence, you need to look kind of outside the mainstream on the margins, um, uh, at, at, at, uh, um, at protests or from, um, civil society groups. So I think of Emma Gonzalez, um, at the March for our lives, um, Gets up to speak and partway through her, uh, speech at this rally, uh, goes completely silent, um, and remain silent for, um, a number of minutes, uh, until people are kind of uncomfortably shuffling around. Uh, wondering if she's lost her nerve, wondering if she's having a panic attack, uh, wondering if she has a huge case of stage fright or something like that. Um, until finally, uh, at the end of this time period, she reveals that she has been, um, silent for the precise amount of time, um, that the shooter in the Parkland. Uh, had dead carried out the, uh, the mass shooting era. Um, so this is, this is really fascinating and interesting to me and moving to me in so many different ways. So one is this kind of connection between form and content, you know, we're, we're, we're totally desensitized at this point, uh, by the idea of a mass shooting. At least I think we are, I think Emma Gonzalez recognized that too. So what is another way to bring this home? What is a way to kind of bring to a mass audience, some kind of the, um, uh, discomfort and wrongness and sense of fear that you might've gotten from living through a mass shooting. And then part of that is figuring out a way to put that into oratory, to put that into words, because, you know, it's almost kind of conveying the sense that we are out of words to convey, you know, the horror of this, because this has been reported to death and spoken about it to death. Um, but there are some things that can only be represented by silence because of that terrible, uh, that's part of it. Um, and the other thing that's interesting to me is this connection between. And you're running a risk and eloquence that I mentioned that this is sort of a, especially for someone like her, that doesn't really have much of a public profile of it isn't wearing at that point, you know, kind of known as a speaker that is just, you know, a high school kid, um, is to take the risk of, of kind of breaking the form in a sense kind of, of taking the risk of not doing what she is expected to do. Um, and risking the people we'll, we'll take it seriously that she's been kind of struck by stagefright or that she's been, you know, paralyzed by the ability to say anything about this, but, but really have it be a kind of a really deliberate, controlled gesture and to be able to, you know, I can only imagine being in that situation and coming up with this idea of how you want to represent, um, uh, this kind of empty, silent space at the center of this experience. Um, And then, and then going through with it and looking at your kind of watch your presumably she's kind of looking at a phone or a watch, just kind of counting down the time. Um, I'm going through with it for one minute, two minute and three minutes. Um, and holding on to this incredibly, uh, uncomfortable situation until she reaches the point at which she had ed exactly. Kind of mimic the time period in which this life-changing event happened. Um, she's, she's a student. She's not a no, no, no. She was someone who is a survivor of the shooting and kind of, um, that's the sort of, I, I can only imagine, not just the experience of speaking in front of a crowd, but doing something kind of that unusual in front of a crowd, but that meaningful in front of a crowd is part of the, kind of this, um, existential quality, uh, Uncertainty discomfort that, that, that a good speaker ought to speak on the course of doing something scary and eloquent. Eloquence ought to be scary to speak around the audience. I did this quote that I made, I made a chapter title, but I keep coming back to it. When I think about, um, Cicero's, uh, mentor, uh, explaining in his dialogue that whenever he gets up to speak, he trembles in his heart. Uh, and, and every limb, um, this idea that, that eloquence and trembling go together because you're really attempting something that is unusual and new and unique and frightening. Um, and I think that public speech for the most part is who kind of stereotyped, um, and stylized these days, that there isn't a lot of opportunity for that. And this was one of the rare opportunities where actually saw those qualities and can only imagine how it must have felt to kind of produce them in, in, in real time. So I wish I'd put that in the book. I didn't find a good way to kind of connect that to the broader themes, but that's, that's what I had in my mind, as I was thinking about, well, where do you find that these days? Um, that was an example that stood out to me. Great. That's really, I mean, that's really interesting. I think. I mean, I'll get onto that, but, uh, I've, I've heard speeches at, you know, live political events. I've found quite moving. Um, and that's typically not what I find when I'm seeing watching television and seeing a high-level politician speak, uh, which, which I'd like to, you know, turn to now, because we've talked about examples of eloquence of rhetoric going well. And there are a lot of complaints about contemporary political rhetoric, especially when you look more directly at how politicians are speaking and a little bit more about the broader discourse. But I think that contemporary political rhetoric is awful. I can't stand to watch polishes and speak a lot of the time and I like to just make some complaints about it and you can tell me why you think it's that way. Um, so one way that. Political rhetoric goes wrong these days. And I don't think I'm anyone thinking of this is that it is incredibly boring. It's bland, uh, to take a local example from Canada, I cannot, uh, I cannot watch Justin Trudeau when he speaks. There are no thoughts that appear in my brain. Um, I get a bit frustrated because he doesn't answer questions, but it seems like so many platitudes that I can't really, there's no edges that I can get a grip on what people are saying. And one of the examples of the same kind of thing you talk about in your book, I think is a Hillary Clinton talking about America is great. And we're great because we're good and we're good because everyone knows it and we're going to value all our diversity and yada yada yada. And it's just kind of a word salad. That means nothing. Um, so it's blend, let's start with that. Why. Our politicians who, you know, if we have any education in ancient Greece, we think they should be standing up setting the rostrum on fire. Their job is at least part public speaking. And yet there they're reading total platitudes from a sheet as though it's their, the first speech they made it, their life made of their life. So what's, what's going on with that. Yeah. What is going on with that? I was thinking about the Justin Trudeau example. I've I've, you know, since moving here, um, I've been exposed to my fair share of Justin Trudeau rhetoric. I think the only kind of, I was thinking like what's the most memorable adjuster Trudeau quote of the entire kind of, uh, uh, prime ministership. And I think it must be when he said it's 2015, um, uh, to talk about the gender balance cabinet, which, which is great, but also like the prime minister's most meaningful statement was just kind of stating what year it was, which was just like remarkable. It has been that many years. That's the, that's the only justice real quick. I couldn't remember. Um, but yeah, so I support you on that. So w what is it? I think, I think there are a lot of reasons. Um, but I think part of it, I think kind of the heart of this is that there's a lot more to lose than there is to gain, uh, with kind of, you know, any in extremes of eloquence or any kind of quality of extraordinary speech, um, any, and part of that is that, that the way that politics has changed that in any kind of, um, um, legislative debate, for instance, um, politicians don't go to the floor of parliament or of Congress to change minds, um, because their responsibility is to their party, uh, and maybe to their constituents, their voters. Um, but they don't go in with the kind of mandate, um, where they are willing and able to respond to persuasion. And of course the people aren't gonna respond to persuasion. Um, then you won't try to persuade them. I think that's part of the reason why there isn't a lot of eloquence, uh, in legislative bodies, but I think in general, um, I think the reason there isn't a lot of political eloquence from politicians. Is because, you know, like I said, um, if eloquence is closely tied to risk, um, there's very little reward that justifies, uh, those kinds of risks. I, you know, I don't think for instance, you know, Hillary Clinton, um, lost because she was a risk averse, uh, speaker, you know, Justin Trudeau has been pretty politically successful as an extraordinarily risk averse speaker. Um, and I think that in addition to the kind of changing risk reward calculus, now, there, there are so many more tools, um, Than there ever have been in the past, uh, for politicians to pursue this kind of, uh, the quality of, of what I borrow a term in the book to call algorithmic rhetoric rhetoric that kind of responds to quantification of what they expect the public is going to accept. And I think part of the reason it doesn't strike people as especially new or risky is because to the extent possible it's calculated to be speech that they're all at Regal and a kind of, not along with, it's not really going to challenge people because you've already done the work of figuring out what people want to hear. Um, yeah. So I think, I think part of it is tactical change. Part of it is institutional change. Um, but I think part of it is he and I struggled to kind of come up with a better way to expressing this. But when, um, rhetoric is first developed as a discipline, it's a discipline, both of speech and division discipline of, of character formation of training, the idea that someone would want to pursue a certain kind of way of speaking to demonstrate their, um, They're their fear or their virtue in the public sphere, public sphere, um, you know, is ultimately, I think kind of a character driven, um, pursuit. And I think it's kind of, it's difficult. I, I don't like people kind of hand waving it kind of a virtue or character of ways of getting politicians to do what we want to do, because it's really hard to, hard to institutionalize that it's really hard to think about that in systemic terms, but I guess what it come down to is is that, um, our political culture doesn't really value, uh, eloquence, uh, and oratory and the orator as a, as a distinctive and kind of unique public figure. Um, and so we don't get that because there's no value, um, to public figures kind of pursue and fill and act out, uh, that kind of role. It's not as if they've lost the ability to pursue those kinds of speeches, just that they have no kind of motivation, either internal or external to want to pursue it. I really liked that idea of. Algorithmic rhetoric, political rhetoric, rhetoric is getting routinized. Um, politicians use all these techniques. They do polls. Uh, they do focus groups and all their messaging. And by the time the politician gets up to speak, they're just feeding back what they know. The public wants to hear. They flattened everything out. Um, but that still doesn't quite give the answer for why it has to be boring. Right? Why is this the main incentive to not mess up or, or to lose anyone rather than to inspire some people? I mean, people do the same thing with Hollywood movies, right. And there was sometimes able to make stuff. People care about, or can I at least sit through for many hours rather than a few minutes? Right. So why, why is the incentive to, to, um, not mess up? I think just because the costs of messing up, uh, in any one case can be tremendous, they can be, you know, I, I think that this thing is sort of thinks about that there could be a career ending, uh, um, you know, in his case it could be, you know, they could lead to, um, uh, actual physical harm. Um, uh, not all politicians face that these days they certainly do kind of take their careers in their hand when they speak. So I think in any given circumstance, the, the, the benefit of doing something inspiring just seems to be so much smaller than the risk of saying the wrong thing and ending career. I don't like to invoke cancel culture because that's just kind of totally stripped a meeting, but I, you have a lot of, I think it kind of speaks to the sense, at least among kind of political and cultural elites, that if they say the wrong thing, the consequences are, um, uh, Are so much worse than the benefit of them saying the right thing and this kind of results in kind of less risky speech. I think the flip side of that is that, um, in the kind of paradigmatic ancient cases, I talk about, you still have speakers facing tremendous consequences. You know, Cicero wouldn't even worry about getting canceled. He would've worried about getting, you know, physically, uh, physically attacked. And I was really, he was assassinated for his, for his political words, right? So it's not as if risks didn't exist, then it's that there was something in Pelling, political figures, I think to go towards those risks, there was something that kind of impelling them to take on risks. They demonstration of who they were and what their character was. It doesn't mean they're kind of better and more virtuous leaders in the ones we have. Now. It just meant that there was some kind of, um, social or cultural or political pressure they faced to do riskier things that came at higher costs of failure. And I think part of that came from. Uh, the outside, it came from sort of populist, uh, bottom up pressure from people who were competing in the same political speech, uh, space. Um, part of it came from, um, did this sort of, uh, difficult and to a Roman, it would have been sort of an encounter intuitive claim that you can demonstrate veer twos, um, his quality of Manliness, by the way that you speak well, how is that? Well, it's by taking on tremendous kind of burdens and risks in the way that you speak that are kind of analogous in the Roman mind to, you know, the really manly things like, like going off to war. Um, you know, I was saying the things that everyone, you know, everyone will accept is just boring and not manly or virtuous, whereas going out there and really putting it on the line with like a, a bold point of view is, is actually an accomplishment that we might admire. I think so. And I think part of the reason. That that, that eloquence changes. And I talk about this a little bit. The conclusion of the book is that most of the eloquence, that we've, that is kind of forms the kind of Western rhetorical tradition comes out of this really kind of circumscribed world of a bunch of elite males doing status competition. Uh, it comes in, it comes from a very kind of, um, circumscribed limited world in which you can win elite, uh, VIR twos, credentials, whether either in the 18th century, British parliament or a needy, uh, first century BC Robin forum, um, by taking on rhetorical risks and by putting it on the line. So you're naturally, you know, our culture, uh doesn't and should not think of public speech in the same way. There's a lot more at stake than which particular elite male gets gets kind of Manliness points. Um, but I, I think that the side effect of, of losing that culture, the side effect of losing the impetus to. Um, pushy leaves to take risks in their speech is a much more cautious and risk averse kind of way of speaking. So I think the way I kind of leave it in the book, and maybe this is the next book, I dunno, I don't have a good answer to this right now, but where I leave it is, um, it's important for us as a political culture to come up with ways of pushing your leads towards political risk and towards risky, difficult, dangerous speech. Uh, for the reasons I talk about these things being valuable, um, you know, without trying to recreate this rightfully, um, and thankfully vanished culture of elite male status competition, how do you get the benefits of that kind of culture with the, without the kind of, uh, baggage that it came with and, you know, this is. I like, I like, uh, I like rivalry and macho posturing as much as the next guy, but I mean, I don't like the more you talk about it, I'm not sure that's something, uh, I want to organize politics around. Right. Um, so, so it may be that if really what this is is about, not, not about kind of evening hierarchal divides and really getting a sense of what the people need and then holding leaders in speakers accountable by making them undergo risk. If it's really just riskiness for the sake of showing off, then I'm not so sure I'm persuaded that eloquence and rhetoric is a great idea and conserve a democracy that, that well anymore and go on. Yeah. So I, I, yeah, I'm really, I, I thought about that too. And I think that's sort of, that's something I've struggled with. I guess, where I come down is that I try to distinguish between. Um, for, you mentioned, like for the sake of, and the side-effects of, um, and I guess when I think about, you know, I come back as sister, because I think he developed a lot of these ideas or, or, or at least wrote them down. Um, I think he pursues a certain kind of idea of eloquence for the sake of winning kind of macho points of kind of demonstrating his virtues. A side effect of this, I think is that he flattens the rhetorical situation and celebrates the ability of the crowd to push back and take a vocal role at rhetoric. Not, not because he's a Democrat, not because he sympathizes with them, not because he wants a flatter politics, but because he sort of has to, in order to have kind of a worthy adversary in, you know, against which to demonstrate his fear twos. So, you know, you kind of. W what I like is the side effect. I think this is the sort of thing where the pursuit of a bad thing leads to a good side effect. And I'm trying to, you know, I try to leave it in the book is, well, how can we, how can we kind of pursue this thing that flattens situations of public speech and public persuasion without the same kind of motivation that, that, that no longer exists and really shouldn't exist. Um, and that that's still, that's still a puzzle to me, but I don't want to write off the side effects and the results of this just because the motivations that get us, there are things that, that I personally, um, and you presumably too, don't really like, oh, well look, I'm, I'm an, I'm an honor guy. So showing off is fine with me. Right. Recognition is a totally legitimate motivation. Um, especially when, when others might not be available. Right. Um, one other reason, uh, that I want to float, why. The fact that rhetoric political rhetoric right now is so boring, might actually be a good thing. Is, is this, uh, a lot of the best speeches seemed to come out of very dramatic, chaotic, risky situations, right? So you think of Winston Churchill, fight them on the beaches beach, something like that. Or, um, speech. These are crisis situations where like there's a lot going wrong. Maybe the reason political rhetoric is so boring is because politics is going pretty well. Uh, there's no giant disruptions or risk it's stable. All the things that we ought to be mad about are not necessarily the crises, but just the slow, ongoing, um, structural evils of our, of our political, our political situation. So, so maybe boring speech just means boring life and boring life is overall better. Like may me, we live in boring times. Right, right. And that's totally, uh, you know, th that that's, that critique, um, has been around for a long time. That that's what a tacit has released. One of, one of the characters that he wrote in the voice I've said is that, um, um, know he says rhetoric. I think that the famous quote is that, uh, that great oratory is like fire. Um, it feeds on things it's burning. Um, you know, the more that it's burning needed writer at the brighter, the flame is so when your house is on fire, um, at that provokes eloquence about it. And I was thinking about, um, when you talk about the kind of grinding structural problems we can't solve, I just watched, uh, don't look up on Netflix a few days ago. And I think a lot of people did. Um, and I was thinking a lot of people have kind of critique this by saying it's supposed to be this global warming allergy, uh, Uh, allegory. Um, and yet global warming climate change, isn't like a comment striking the earth at all. It's not this kind of like deadline thing where the clock is ticking down. This is kind of boring, structural, systemic thing that, um, is not going to change noticeably in anyone's lifetime, which is what makes it, so devilishly hard to deal with. So yeah, that, that is like, how do you, um, maybe problems like that and times like this, uh, even like the pandemic don't produce great oratory. Um, so I, I, I think there's a lot of truth to that. Um, but I also think, um, One of the things I talk about in the book is Edmund Burke's response to this is he's he's critique of this position. Um, that, that struck me as having a lot of, uh, plausibility, which was that sometimes the relationship can go the other way around because language itself is powerful. Sometimes the right kind of language can, can wake us up in a situation in which we've kind of been numbed, um, or kind of lulled to sleep by the nondramatic nature of our problems. And that sometimes language that is, um, has this quality of sublimity, um, which is, you know, this kind of quality of, um, uh, striking fear into people or over the top newness and not kind of fear of, um, You're not that kind of fear of personal danger, but, you know, awesome. A and a sense of kind of awesome originally meant, um, rhetoric that is sort of, um, uh, deliberately on inspiring, at least in the way the Burke thought about it can wake people up to look at their situation there in more clearly, because sometimes, um, you can kind of get in a destructive cycle in which events are boring. So speech around them is boring and people kind of get lulled to sleep and they can't deal with the crisis that arrives in their events because they're kind of asleep. Um, and Brooks thinking of language, at least thinking around language at least was the idiot that language itself can sometimes take priority that the right kind of pursuit of sublimity. Can shake people up so much that they sort of kind of sit up in their seats. So their vision has clarified that they look at political events with the news kind of sense of, uh, perception and clarity, um, and can judge where they are a little bit better. Um, and I don't know if that's kind of, I think that's an empirical question as much as the theoretical question, right. You know, to the extent that kind of the, the tasks of T and speculation about this is also theoretical. Um, what if, um, boring times lead to boring rhetoric? Um, I think it's kind of fair to respond to it with another, what if question, which is what if language can have priority sometimes and can wake us up, um, when we've been too bored to respond to the problems in front of us. Um, right. I mean, those are two distinct cases, right? Because, um, I, maybe I muddied the waters by throwing in the grinding structural problems, but there's one thing to say, look, we want boring politics, exciting politics are bad because people usually dying right. And therefore if, if the cost of it is that we have boring rhetoric fine, but then there's a separate point that you're making that I also think is really interesting and quite plausible, which is that when there are real problems that people are asleep to rhetoric may be the way to wake them up. Right. Right. And maybe we need some excitement when there is an defacto crisis that people are not noticing. Yeah. But that's more of identifying, identifying it, you know? Yeah. So I think in the first case you're talking about kind of the, which is a kind of thing for the more challenging response is like the boring times, uh, boring speech. Everything's great. And I think that. Yeah, I think that's fair. Um, I guess this is what we, we wanted modern government to be, right. So we don't want, we don't want this Athenian, this fickle Athenian mob going left and right. Making all these decisions, going to war for glory, et cetera, it was let's do some, you know, let's do a cost benefit analysis. Let's do that in committee. Let's analyze it and then just explain the facts to people and, uh, you know, no retinol, no quick turns. And so there's no reason to get everyone standing up a standing ovation is probably a sign. People are not doing things at the right pace. Yeah. That's sort of the, sort of the enlightenment dream, right. That that's the sort of human essay, uh, that, that politics may be reduced to a science that sort of the goal of that kind of school of thought. And I guess, you know, the, the, the way I think about it is I think that that's, um, you know, uh, it's good in theory to take this the podcast. I think that that's, I think that of in theory makes sense, but I also think. Yeah. When you talk about boring politics, that always raises for me the question of boring to who it's always that boring and whose terms. Um, I would say that, um, even in situations, in which politics are kind of normal, uh, and technocratic and ordinary and not dramatic, um, there are still, uh, power differentials. There are still haves and have nots. There's still winners and losers. There's still justice and injustice. Um, and politics, I think can be very outwardly boring maybe because you live in kind of a sort of, um, ideal state of good government, or maybe because you kind of live in a state of, uh, ideological hegemony, uh, and that the, the powers that be, um, have so much control over the ideological apparatus and so are so good at, um, at, uh, generating consent that there isn't really a challenge to, um, uh, to, uh, Their priorities and their sense of what makes politics boring. You know, I think about, you know, I go back to the original way that tacit has raised his point, and this is kind of why I attributed it to the guy in the dialogue rather than Tacitus themselves, because there's a lot of like, you know, do you really mean this? Was he speaking to someone's mouthpiece, a task? You know, supposedly Tacitus is a guy who hated, um, uh, the Roman principle who hated the Vivi empire, who wanted to be, uh, who wanted to return to Republican politics. Uh, and has this guy in the dialogue say, well, now that we have kind of the wisest citizen in the state running things, we now we have administration rather than politics. Uh, things are boring and it's good to speeches and exciting because they're, those were the battle times and the civil war, um, which. Tough because on the one hand it has a flavor of plausibility, but on the other hand, then, you know, the politics he's describing as boring is the politics of kind of domination by the emperor and his household is the politics of, um, um, I think Tacitus also wrote this kind of famous line. They, they, they create a desert and they call it peace. It's this idea that you can have boring, peaceful politics, um, because your government is so good that no one has an objection or also because the kind of domination of the ruling class is, is so complete, uh, that no one thinks raising objections, the silence of despotism and sorry, it's hard to say which situation you're in. Certainly that that's not what the kind of enlightenment critique of rhetoric was aiming at. But I also think that it kind of, it's hard to tell from within a moment of boring politics, whether politics is, um, uh, you know, whether it's a. Boring for a reason, a or boring for reason B I say that someone grew up in the nineties, um, anytime I've kind of Eve the famously boring end of history. Yeah, exactly. Which, which turned out not to be rich, which, which like, um, which, which makes you wonder what kind of boarding where we living through. Um, yeah. So enough of a boring rhetoric. Well, um, I want to talk, I brought that up by saying that there's a few ways that contemporary political rhetoric seems to be going wrong. Uh, and the other big one is there's a lot of complaints, not about boring establishment rhetoric, but about insurgent populous rhetoric. So there's lack of decorum. There's a end of civility. You've got Trump making fun of people and throwing insults around. People are willing to say things that they wouldn't say before. Uh, people are getting, you know, speaking. In very conversational, not stylized terms. So there's this, this other critique of political rhetoric. That's I think talking about a completely different kind of rhetoric. So why do we have that trend as well? Yeah, I, I think we have it in kind of a response to the kind of pathologies of establishment or mainstream rhetoric that I've been talking about be kind of pathologies of risk aversion, because I think that the one thing that is, so it stands out to me about the kind of populist Trumpian take a kind of clear example rhetoric. Is this the, the, the appearance of, um, uh, Risk acceptance the appearance of, of tremendously dangerous speech that could supposedly sink this guy to any kind of given moment. This is sort of the reason that I think that back when he was first getting on the national stage as a, as a presidential candidate in 20 15, 20 16, anytime Trump opened his mouth, every network would cut to him because the, the presumption was that, um, he'd say something fun to watch. It's gonna be fun to watch, and he's going to, he's going to put in his foot, and then he's going to say something that's going to be so bad as from destroy his career. We're all gonna watch this happen in real time. And it's the kind of tight roadblock of watching it happen. But, um, I think the problem is, is that with hindsight, it's turned out that a lot of this appearance of, of, of your right of walking the tight rope is that there's very clearly a net like one foot below the tight rope, which is that he's not really taking on those risks as he's speaking to, uh, He's speaking to audiences that are prime to agree with him. He courts, you know, there's so many scams at the same time that nothing exactly breaks through. Um, and also, you know, he's, I, you know, I think I say this in the book, but when, when I say that he's incapable of shame, I'm not saying this, that, that, that he's a bad, and unvirtuous person, I'm saying that shame is an important part of public speech. And that it kind of means you're responding to negative feedback from the audience. If you don't have that stimulus. So you kind of can't, if you can't feel that like you can't, someone might not be able to feel pain. He was trembling in his heart and in every limb, because he had a strong sense of shame. If he got booed, he would have been mortified. And it might've been career-ending. Whereas Trump, he gets booed, he loves it, and his support just becomes stronger. So the incentives are all. Yeah. And I think, I think he responds to maybe booze from his kind of particular audience. So you've had of course a, you know, his, his, for, for his base. But I think, you know, there are other people that simply don't have kind of standing to object to him as a, uh, as a political figure. So really like the risks that he takes on in any given appearance, it seems enormous at first glance. Uh, in reality, I think not so much. I think he kind of gives the appearance of what we actually would like rhetoric to look like. So when I think about, um, why, why do people connect with, with figures like here? And I think it's because they seem like they are offering something that we are missing, uh, even though they aren't really doing that. Um, but I think that they are filling, um, they're meeting a real need. The need is out there. They're just kind of meeting it and kind of a cheap sort of fast food way to kind of mixed my metaphors. Right. Okay. So we have Trump and different other sort of demagogic type speakers because mainstream political speech is too boring. It's just platitudes. It's already been focused groups, death. There's we're not hearing anything there. So someone comes on, they're saying things that sound risky, but you're saying, you know, people are looking for that risk, but there's actually no risk at all. So it's not what it looks like. I want to put you a different reason. It's not so much. Okay. So why is it about risk? So for me, I will watch, I will read Trump's tweets or watch him speak for pure entertainment value more than I would most other politicians. I would rather watch Joe Biden speak off script and spin me a yarn about a life in the fifties or, or, uh, then watch him from the speaking from the teleprompter. I'd rather watch, uh, Rob Ford's take a local example than his brother, Doug Ford as premier, right? He's going to say something that doesn't sound completely scripted when the script writers, no offense, uh, are writing really boring material. Um, so is it is the appeal of Joe Biden, mumbling, a yarn, really? That people think he's going to fall on his face and ruin his career? Or is it just more interesting to hear? Uh, same with Trump because after a while everyone saw the trick, no one thought that him being shocking was ever going to ruin his career. That's what had made his career. Um, so. There's a little more to it than we just need to see people take risks. Isn't it? Yeah. I think that's fair to say. I don't maybe made a I'm exaggerating when I'm saying that the costs of Trump doing something badly are going to ruin his career because obviously, you know, we've been through many years of this and he has not said the career ruining thing. I mean, he, um, uh, he, you know, he tried to overthrow the government, he sees the leading, uh, Republican nominee and the next election. Right. So, yeah. Yeah. So I think that maybe that's not the right way to put the kind of downside risk in term, uh, the terms in which to put the downside risk, but I still would say that, that part of the interesting thing, know, at least speaking intuitively watching Joe Biden tell that yarn or watching kind of a Trump do one of his kind of freeform riffs. Um, yeah, it was this idea that it kind of, um, it's just this quality of spontaneity, so you don't know where it's going to go. It could be, it could pay off tremendously. It could have a great kind of ending or a punchline. Um, it could end up, uh, in a, it could just end up going badly and giving you kind of that sense of aesthetic. Um, it could end up being, you know, embarrassing the speaker. I may, it might at the extreme in his career. It probably won't any given instance, but I do think that there's kind of that sense of unpredictability that includes consequences and sanctions for the speaker. Um, that most mainstream political speech is sort of designed from the standpoint of avoiding, um, that it kind of starts in that standpoint and works backwards. You know, I think that the standpoint that I think mainstream political speech starts from is, um, um, what, what, what words work? What does the audience want to hear? Um, what, uh, what, what words move the lever or press the button that results in the political result I want with a smallest cost to me, uh, what are they? And I'm going to go out there and say them. So I think that the whole performance has kind of given, um, you know, we know from the perspective, the out the opposite of spontaneity from the opposite of, um, um, From the art from a position of trying to maximize certainty for the speaker, rather than trying to maximize, uh, interest, um, and engagement from, from the people listening. You know, I think that that's why a lot of people have talked about. You know, Trump, for instance, uh, as a humorous or talked about is kind of the connect from me, demagogic power and joking and humor. I think one of the things that that makes humor work in general is, is unexpected. You know, punchlines are surprises there when statements go in directions, you're not expecting and they kind of trigger your flight or fight response, and then they get resolved in a way that makes you laugh. Or at least that's kind of one theory of what humor does a kind of incongruity idea of humor. Um, and I think you can kind of generalize that, to say that part of what makes this kind of non-mainstream non scripted, or even if it's Joe Biden kind of rambling speech is this quality of unpredictability, which, which includes the possibility of it going badly for the speaker. But even if it doesn't go that badly, even if kind of, you know, Joe Biden kind of, um, uh, rambles on and embarrasses himself, isn't going to end his career still might make him look kind of like a bit kind of daughtering out of it or in Trump's case. Um, look as if, um, look as if he said something kind of with, with this utter sense of shamelessness, um, in either case. I still think that there's a kind of quality of putting more on the line and the ordinary speaker kind of wants to put on the line and to, just to, uh, say something about shamelessness. Yes. Trump is shameless in what he'll say, but I think there's also a certain kind of, if you think putting it on the line by saying what you think is something worthy of respect, then there's a certain kind of shamelessness to be willing to get up on a speech and get up before a crowd and read a speech of statements that have been focused group. Just because you think that people like to hear them to try and press buttons in that way. That's like utterly shameless from a certain point of view, uh, as well. Yeah, I think so. Um, okay. So I've talked about, you know, we've talked about two ways that contemporary rhetoric is going badly. One is that established rhetoric can be incredibly boring too, that there's this other kind of rhetoric that people seem to be really interested in. It's more entertaining, but, um, nonetheless, uh, isn't giving us what we want from rhetoric and also might be damaging civility and decorum. Um, what would it take to have good rhetoric or eloquence now? And do we want it, do we want it? Well, I think we do want it to the extent that we are still in a situation, um, in which politics is, uh, um, is asymmetrical and which few speak in many lists. And, you know, to the extent that that's the way that our politics, you know, politics is to the extent we live in, you know, Jeff Brene talks about politics and spectatorship to the extent that we are, uh, As ordinary people in many ways, spectators to politics and not actual political actors. I do think we want our politics to be, um, more unpredictable, um, or kind of shaped by, by, um, rhetorical risk and therefore kind of more eloquent, uh, because of the side effects I talk about in which kind of tend in the direction of political equality, I think. Um, but how do we get there? Well, that's, that's, that's tough. Um, I think that one thing I'm trying to develop in my next, um, um, in my next project, which I'm still kinda, I'm, I'm still trying to figure out, but is the way in which a lot of the Smithsonian ideas of rhetorical risk that I, I talk about in this book are developed in response, not just to kind of this argument within the Roman elite, but in response to the pressure from the bottom up. So that tells me something that, that. It's, it's not politicians spontaneously deciding they want to be more riskier, spontaneously deciding they want to pursue eloquence or spontaneously, you know, developing the virtue to pursue it. It's that these things develop when there are publics who demand it, these things develop when there is a public demand for politicians to behave in a certain kind of way. So I guess that tells me that I don't have an answer to how to how this is going to happen. Right. Cause if I did, I'd be doing it instead of writing competitor. Right. You know, and I might say that the way you get publics who will make these demands is right. Or to have publics who like have some kind of institution to make themselves heard. Yeah, sure. And I think that, I think that eloquence happens when publics place a value, um, on eloquence, I think this is Ronnie eloquence develops, uh, in a context of, of bottom up pressure. And I guess what I'm, when I'm writing about, hopefully my next book is about, um, hopefully about race and American oratory and the way these kinds of questions about, um, eloquence and access to the public sphere. Um, when people from oppress groups and especially here, I'm thinking about, uh, black workers in the 19th century, like Frederick Douglas, um, claim the right to be heard in the public sphere. Um, in a way they hadn't previously been heard before and how this changes the way the public thinks about eloquence, but that that's all of the project. But I guess my point is is that if anything is going to change, this is going to be because, um, there there's public pressure on politicians to be less predictable for reasons of promoting, um, more equity in the, in, in political communication, more equity in politics. Um, is it going to happen? Who knows? But I do think that it's not going to happen spontaneously because politicians suddenly decide that they want to start sounding more, um, Cicerone or Kennedy, escrow, whatever it is. Well, I, when we spoke a little earlier about the different contexts they have in which to speak, or if you even think about the career trajectory of a contemporary politician, Eloquence doesn't seem to matter that much. I mean, it did kind of for Obama, he gave a famous speech and then, you know, he was kind of a, a big prospect to be the presidential candidate. But I mean, if you w what's the path to becoming an MP, right. And then what's the path to getting into cabinet, and then what's the path to becoming a leader. It's, it's not generally through speechmaking. And once you are in office, as you said, speeches on the legislative floor on parliament floor, they're not going to persuade anyone. Um, if anything, they're for soundbites for television. Uh, so, so maybe people who have independent, you know, if they're going out and doing rallies with their supporters, that's an occasion maybe for rhetoric, but even then, you know, the chances are, you're giving it to supporters. They're not going to boot you. So. It just seems that there's not even many contexts, like even if a politician wanted to be more, uh, eloquent, where would they get the practice? It's not part of their life, the way it was in Greece or in Rome. Right. And I think that, yeah, I think the way I, the way you describe it makes a lot of sense to me is this idea that I, you could think of it as kind of like a satisficing thing in, in the political culture you're talking about. There might be a kind of minimal bar that you have to clear. You can't make an ass of yourself. You can't do FPL to string sentences together. But I think few people, I think about Obama as maybe a partial exam exception, but few people kind of ascend to political office on the string to that, you know, simply because that's right. That's not what our political system, um, select for or values. Um, so is that. Is that a good thing? Are we selecting for other good things that we like instead of that? I mean maybe, but I, I think that, I guess part of the case I'm trying to make in the book is that when you stop selecting for this, when you stop paying attention to this, as something that, that a, um, public figure ought to cultivate and develop, um, you lose out on things as well. And I think part of what you lose out on, um, is the ability to kind of engage the public, uh, from a bit more of a perspective of, of equals to treat them with that kind of regard and respect that takes our views seriously, which is, I think kind of what rhetoric is all about. So it's, you know, a lot of people think of eloquence is kind of a way of, of, of, of, uh, of dominating, uh, of, uh, of, of generating ascendancy over the people you're listening to, you know, but I really think about it in different terms. I think about it as, as caring enough about. The, uh, individuality of the people you're speaking to, uh, to try to impress them, to try to win them over, to try to, um, create some kind of degree of beauty and public life. Um, if you're not, if you're not trying to win them over, that means you don't really care what they think. Yeah, I think so. Or you care what they think to the extent that you can cut to instrumentalize it, that you can kind of figure out what they think beforehand and then deliver, you know, the, the words that you think are going to work. Um, but again, that's not, uh, you know, that, that's the kind of thing that we saw in interpersonal relationships. Um, we would think about it as sort of, um, you know, tremendously manipulative or instrumentalizing, you know, imagine that I'm sure people do this, are you, you get mattress on our dating app and imagine that you then, you know, kind of use an algorithm to figure out exactly what kind of conversation topics they would like and then drop them into conversation. Um, if you did that in an interpersonal relationship, I think you'd, you'd be, you'd be a creep. Um, but I, I think that this is essentially what a lot of political communication boils down to. Um, and I think. You know, because we have a political culture in which, um, the tradition of eloquence doesn't really get valued in the way that I've described. I think you have politicians who are much more inclined to instrument instrumental as the public, you know, so again, I think eloquence is, is intrinsically valuable because it's, it's aesthetically beautiful. To me, it's important to me to have a public sphere in which, um, we have aesthetic values that are recognized in the way we talk and then comport ourselves. But even if you don't, even if you write that off, I think that the pursuit of it has some kind of valuable, uh, knock on political side effects, um, of the kind that I've been talking about. Yeah. I mean, look, I would love to, I would love to be interested when I hear politicians speak as well. Yeah. Well maybe not, maybe it means we're heading towards doom. Right, right, right. You know, maybe, maybe the fact that things are so boring now, uh, means that there's big opportunities for people who do move towards eloquence. And this might be what it is. You know, a kid that anyone who speaks at all well, we'll stand out so much that, uh, there might be some incentive sort now. Possibly. Yeah. All right. Well, thank you so much for being on Rob Goodman. Um, thanks for writing the book words on fire eloquence and its conditions. Is that right? That's right. And that comes out this year or is it, is it, it came out, uh, just a few weeks ago. Okay, great. So anyone who is interested in the conversation go have a look for it, uh, wherever you get your academic tomes. Um, thanks a lot for being on and, uh, yeah. Hope to hope to hear about your next project. Thanks so much for having me on. I really appreciate it. Thanks for. Today. I want to send a big shout-out to my man, Ethan Denney. Congratulations on absolutely killing it in your first philosophy course ever. And also thank you for deciding to support us on Patrion. We hope we're of some use to you. If you dear listener would like to support the show, head over to patrion.com/could in theory rate and review the show on your podcast app. Grab someone else's phone and subscribe to good and theory so they can enjoy it too. Thanks for listening. Catch you next.